Tungsten and other useful things

Time for a little perspective on strategic minerals and global supply chains

I’m bored so we’re talking about industrial metals today. I know, that seems like a non-sequitur. Who fights boredom with industrial metals? Engineers and crazy people, that’s who. I guess knife-wielding serial killers as well.

Among the many useless government agencies is the U.S. Department of the Interior, which does include one potentially useful part: the U.S. Geological Survey. The USGS produced a report called Mineral Commodity Summaries 20201 and it’s every bit as exciting as you might expect.

From the extremely dramatic and gripping Introduction:

Each chapter of the 2020 edition of the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) Mineral Commodity Summaries (MCS) includes information on events, trends, and issues for each mineral commodity as well as discussions and tabular presentations on domestic industry structure, Government programs, tariffs, 5-year salient statistics, and world production and resources. The MCS is the earliest comprehensive source of 2019 mineral production data for the world. More than 90 individual minerals and materials are covered by two-page synopses.

I can’t believe you actually read that part. Sucker. So what is Tungsten used for? Why am I bothering to type a boring Substack post about it?

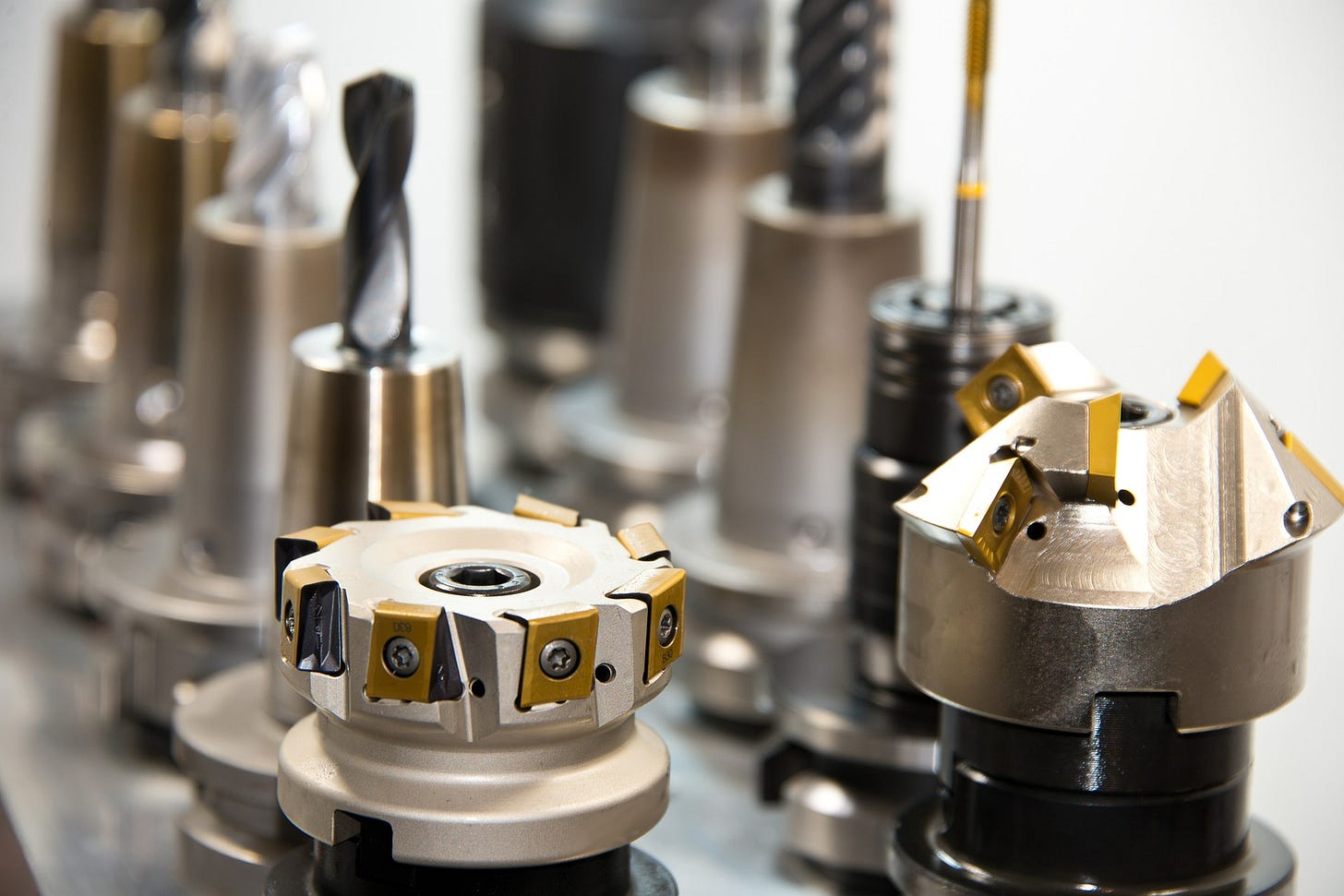

Nearly 60% of the tungsten used in the United States was used in cemented carbide parts for cutting and wear-resistant applications, primarily in the construction, metalworking, mining, and oil and gas drilling industries. The remaining tungsten was used to make various alloys and specialty steels; electrodes, filaments, wires, and other components for electrical, electronic, heating, lighting, and welding applications; and chemicals for various applications. (USGS Mineral Commodity Summaries 2020)

Well, it’s not like the construction, metalworking, mining, and oil and gas industries are important. And heating and lighting are very overrated.

Let’s jump over to a website that’s all about engineering materials, azom.com for the world’s shortest history lesson about tungsten2. I suspect these folks go on fewer dates than I do (so a negative number of dates).

Tungsten (W) was one of the first alloying elements to be used methodically—as early as the mid-19th century—to enhance the properties of steel. One of the most significant alloying elements in constructional steels and tool steels, tungsten was added to improve the cutting efficiency, hardness, and speed of tools. (azom.com)

Without tungsten all sorts of industries run into trouble as soon as their existing tools wear out. There was just such a shortage of tungsten during the second world war, and an alternative was developed for for one type of steel, called high speed steel (HSS).

During World War II, due to the shortage of tungsten and growing demand for tools, the U.S. and European steel manufacturers were forced to find an alternative. Molybdenum (Mo) was selected as a substitute to tungsten in varying proportions. This was also economical as the cost was lower, and the atomic weight is only half that of tungsten (1% Mo is approximately equivalent to 2% of W). (azom.com)

So despite domestic production, the supply of tungsten in WWII was limited enough that new alloys were developed to try and fill the gap. Unfortunately HSS can only be used for some cutting applications.

Tungsten is very critical for manufacturing, so how much tungsten is produced in the U.S.?

There has been no known domestic commercial production of tungsten

concentrates since 2015. (USGS report)

Zero. Boy, I sure hope we’re not about to get into World War Number Three anytime soon. It’s hard to make tanks without cutting tools, unless your tanks are made of play-doh.

So where do we get all of that thing that’s super critical for all sorts of heavy industries?

World tungsten supply was dominated by production in China and exports from China. China’s Government regulated its tungsten industry by limiting the number of mining and export licenses, imposing quotas on concentrate production, and placing constraints on mining and processing. (USGS report)

From China of course. The report provides nice little tables for each mineral type and China is supplying over 80% of the entire world’s demand for tungsten.

It’s not like the U.S. doesn’t have any. We just don’t mine it because we’re too busy mining Bitcoin instead.

World Resources: World tungsten resources are geographically widespread. China ranks first in the world in terms of tungsten resources and reserves and has some of the largest deposits. Canada, Kazakhstan, Russia, and the United States also have significant tungsten resources. (USGS report)

Well, those resources are only significant if we use them. Otherwise they’re just fancy dirt. There are some substitutes, but these only replace a small amount of the total we use.

Substitutes: Potential substitutes for cemented tungsten carbides include cemented carbides based on molybdenum carbide, niobium carbide, or titanium carbide; ceramics; ceramic-metallic composites (cermets); and tool steels. Most of these options reduce, rather than replace, the amount of tungsten used. (USGS report)

Side trip to talk about armor piercing ammunition

Why? Because I’m an engineer and this is the kind of thing we talk about.

One interesting use for tungsten is armor piercing rifle ammunition. This is the cartridge for the M16 rifle and M4 carbine used by the U.S. military:

The military doesn’t use this ammunition for all purposes because it’s expensive, but the the good news is that we have an even more expensive substitute: depleted uranium.

Potential substitutes for other applications are as follows: … depleted uranium alloys or hardened steel for cemented tungsten carbides or tungsten alloys in armor-piercing projectiles. (USGS report)

Hardened steel is much cheaper than tungsten but doesn’t work nearly as well. Depleted uranium (DU) works even better than tungsten, and is a byproduct of the process of uranium enrichment to create U-235 for nuclear power plants3 (and nuclear weapons). We had plenty of it when the Department of Energy was enriching uranium but we don’t build a lot of those nuclear plants anymore.

The DU is also still radioactive so don’t use it at your local shooting range. Unless you want that range to start glowing in the dark after a few years of use. What I’m saying here is that you probably don’t want to use it for small arms ammunition unless you really have no other choice.

Well, it’s actually alpha particle radiation so it’s really only dangerous if you inhale it. Feel better now?

In a much more mundane application, tungsten is used to make high temperature steels. Where do we use those?

Heat-resistant steels are chromium/nickel steels consisting of up to 6% tungsten. The steels are mainly used as valve steels for combustion engines, with about 2% tungsten.

For example, such steels are used for the valves on the outlet area of automotive engines, where the red-hot hardness has to be integrated with high-temperature corrosion resistance. (azom.com)

No big deal - it’s just the whole automotive industry except for the Tesla part, which I suppose is a selling point for electric cars. Of course those use massive quantities of other minerals mined by underage children in Africa.

Just kidding - I haven’t looked up all the minerals used to make lithium ion batteries for electric cars. Lithium, though, is definitely one of them and it’s another example of something the U.S. has large reserves of but almost no production.

Similar to tungsten, almost 80% of the world’s lithium comes from just two countries: Australia and Chile. From that same USGS report:

Lithium supply security has become a top priority for technology companies in the United States and Asia. Strategic alliances and joint ventures among technology companies and exploration companies continued to be established to ensure a reliable, diversified supply of lithium for battery suppliers and vehicle manufacturers. (USGS report)

Imagine that: two minerals, without which the automotive industry is nearly crippled, are almost entirely imported. To make things more risky almost all production is from just three countries.

These are the things I worry about at night, which is why no one likes talking to me unless they’re already in a bad mood.

The not so subtle point

In the modern world we are incredibly dependent on foreign trade to keep critical industries running, even in the case of natural resources we possess in abundance.

If we experience some event with global consequences (like a war with a real country, perhaps China) we can in theory produce these minerals ourselves, but getting industrial-scale production up and running can easily take years.

In the geopolitical sphere, this is something we need to keep in mind when discussing national security - it’s about more than just how many tanks (and ammunition, and other things) we have, it’s also about how many we can build. Without China’s cooperation that won’t be very many for a while.

Original:

https://pubs.usgs.gov/periodicals/mcs2020/mcs2020.pdf

Archived copy:

https://web.archive.org/web/20220224104514/https://pubs.usgs.gov/periodicals/mcs2020/mcs2020.pdf

Original:

https://www.azom.com/article.aspx?ArticleID=1264

Archived copy:

https://web.archive.org/web/20220303045943/https://www.azom.com/article.aspx?ArticleID=1264

EPA on depleted uranium:

https://www.epa.gov/radtown/depleted-uranium

Archived Copy:

https://web.archive.org/web/20220303052724/https://www.epa.gov/radtown/depleted-uranium